Fitting the Pieces Together: how to solve London’s co-location puzzle.

Recently, I found myself in a ‘Housing Conference for London’ workshop set-up by Sadiq Khan, Mayor of London. The section of the workshop I attended was predominately for people in the ‘industrial’ world to come up with ways to solve London’s housing problem: in essence, how can you fit the current and future industrial requirements on less land, thereby providing more space for much needed residential? This issue is not new, and whilst the industrial sector has been bemoaning the loss of industrial land – myself included – there don’t appear to be many options, particularly when green belt remains sacrosanct, and even this wouldn’t provide the answer to the scale of the problem facing London.

So back to the Mayor’s workshop. It became apparent, very early on, that all the attendees – developers, local authorities, architects, GLA, advisors – had different views on what ‘industrial’ means. This got me thinking. For us to sensibly look at locations for housing industrial, co-location, mixed use, multi-storey etc, surely, we need to have a clear view on the type and mix of these uses and their compatibility with existing homes and businesses. A parcel operator, for example, is very different to a company that provides 3D printing. Likewise, a food production facility has very different needs to a builders’ merchants, and so on. I would contend that the current use classes aren’t as much help as they should be in this process.

So how do we try and break these uses down or categorise them in a way that will help us understand the possibilities of how they could be accommodated for in the future?

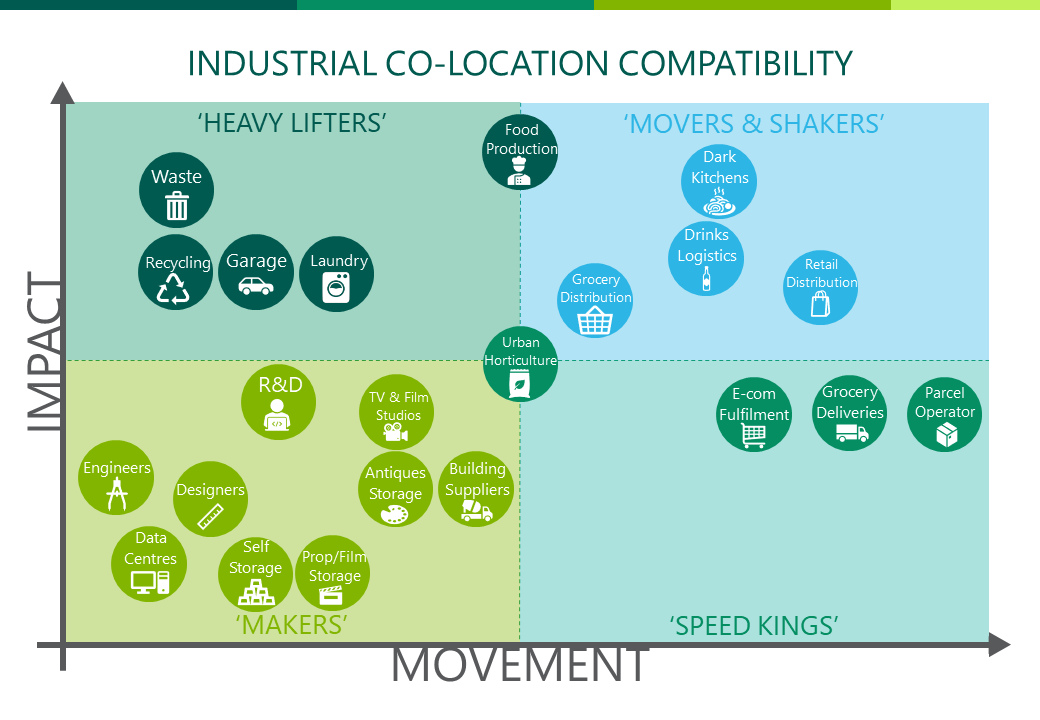

Imagine a graph with movement (that is predominantly movement of goods which will translate to movement of vehicles and to a lesser degree people) on the X axis. On the Y axis would be impact (so that might be the times of operation or the noise/smells/nuisance and even visual impact coming from the facility).

Plotted on to this graph are the different ‘industrial’ uses we find in London and an estimate of where these would sit in terms of their impact.

So, on this graph, everything but the bottom left segment would undoubtedly be the least attractive to locate close to residential. Imagine having purchased a flat in a trendy new apartment block only to find you have a noisy industrial neighbour who needs to work through the night to service the London market. Whilst you might appreciate the need to deliver products to the Capital 24/7 and wouldn’t object to similar facilities elsewhere, you would probably consider it an undesirable addition to your own neighbourhood. In contrast, uses in the bottom left would almost certainly sit well in a planned mixed-use community, in fact it could create a vibrancy that most people would welcome and be attracted to.

We are obtaining data to understand how much space (sq. ft) is currently used by these different segments throughout London. Our current guesstimate is that, unfortunately in terms of solving the housing problem, the bottom left is by far the smallest by area.

How do we use this information? Well I believe we need to proactively encourage the uses in the bottom left into mixed use communities – on the basis that the other ‘industrial’ uses are less likely to fit as well. This could be through planning policy, rates savings, other state intervention and a cultural shift in how we placemake ‘industrial’ in the UK.

If we can actively move all the bottom left, let’s call them the ‘makers’ to mixed-use schemes, we need to ensure that the sites they free-up in traditional industrial locations, where people wouldn’t want to live, are kept and protected only for the other boxes. These businesses are critical for London to function. In simple terms, without these businesses being embedded in the fabric of London, it will struggle to feed and clothe itself – or certainly at the speed and volumes a modern world leading city requires!

HEAVY LIFTERS:

- Heavier operations essential to the smooth running of The City.

- Potential high levels of noise or another nuisance.

- Examples include waste management companies and laundries.

MOVERS & SHAKERS:

- Storage and distribution of goods and products essential to London homes and businesses.

- May operate 24 hours a day.

- Examples include food and drink deliveries and dark kitchens.

MAKERS:

- Smaller, specialist industrial businesses including start-up enterprises.

- Generally, only active within daytime working hours.

- Examples include engineering companies, designers and antiques storage.

SPEED KINGS:

- Fast moving operations with significant vehicle numbers and movements.

- May operate 24 hours a day.

- Examples include parcel delivery companies.